'It’s seriously worrying': Cameraman focuses lens on our planet amid climate 'breakdown'

Cameraman Doug Allan is on the road with a new show – Wild Images, Wild Life – highlighting his career and his concerns.

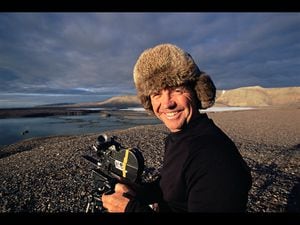

No cameraman on earth is as capable of capturing our vanishing planet as skilfully as Doug Allan.

The award-winning photographer and wildlife cameraman has been the recipient of the Fuchs Medal and the Polar Medal (twice). No other cameraman is as experienced filming in polar regions – whether on the ice or diving under it.

Allen spent ten years with the British Antarctic Survey before becoming a natural history cameraman and presenter. He has won countless awards for his photography, on programmes including The Blue Planet, Planet Earth, Life, Human Planet and Frozen Planet.

As a child, he became a keen snorkeller and underwater diver, which inspired him to study marine biology at the University of Stirling. His first job was as a pearl diver with Bill Abernathy, the last pearl hunter in Scotland. By 1985, he had become a full time cinematographer and since then he has won eight Emmys including “Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming in 2002, for Blue Planet, and in 2007, for Planet Earth. He has also won four BAFTAs and in 2017 won an outstanding contribution award at the British Academy Scotland Awards.

Allen is back on the road with a new show, Wild Images, Wild Life, which reaches Shrewsbury’s Theatre Severn on November 12 and Brierley Hill’s Civic Hall on November 13 before ending at Stafford Gatehouse on December 1.

Allen says: “I want to persuade people to come on an emotional journey with me, a journey with a message but which is also infused with humour and raw adventure. In the show, I’ll be looking back at the highlights of my 35-year career, and chart my feelings during that time. It started with pure excitement, but over the years it has evolved into a greater appreciation of all the experiences I’ve had. When you work with animals like polar bears, it’s a wonderful privilege.”

Though the tour is entertaining, it is also deeply important. The planet is changing at a dizzying rate as we lurch headlong into a major environmental crisis. The protests by Extinction Rebellion against our warming planet and the lack of political action to tackle that has elevated environmentalism into the public conscious.

Allen is aware of people’s concerns: “My quiet appreciation has now given way to deep concern. I’ve spent a disproportionate amount of time at both poles, and over the years I’ve seen many changes. Being a scientist before I was a film maker has allowed me to understand the full implications of climate change, and it’s seriously worrying. It’s more accurate to describe it as climate ‘breakdown’ rather than climate ‘change’.”

More than most, he is able to note the differences. And while climate change is only now being taken seriously, he says the effects have been apparent for decades.

“I first started to notice the difference when I was working in the Antarctic in 1976, there were a few murmurs about climate change, but not much concern. Then when I went to the Arctic for the first time in 1988, that’s when Jim Hansen, the renowned American climate scientist who at the time worked for NASA, first said, “Hold on, I think we have an issue here with a warming planet.” Things were slowly starting to change. Back then for example, it was a case of snow in spring in the high Arctic, but by the 2000s that snow in May was now falling as rain. The melt on land and the break up of the sea ice was happening earlier every year. I’ve watched those changes in the Arctic with my own eyes.”

There have been other occasions where the devastating collapse of our natural ecosystems has been apparent.

“I worked on the BBC’s Life in the Freezer in 1992. One of the big sequences in that series involved filming penguins on Dream Island in Antarctica. At that time, there were about 18,000 pairs of penguins there, but when we returned to Dream Island for another series in 2008, the numbers had reduced to only 3,000 pairs. That’s a precipitous decline. Talking to scientists, they’re concerned because the fastest warming places on the planet are the poles. Temperatures in winter on the Antarctic Peninsula are now 5 - 6° warmer than they were in the mid- 1950s. That’s caused some radical changes. Increased melting of the glaciers and ice shelves is already beginning to increase global sea level.”

Allen has made many films for NGOs. The Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean were once one of the most pristine of coral reef archipelagos, but now they’re blighted by a hellish amount of plastic. When he filmed there he also saw widespread evidence of coral bleaching, which is where the water gets too warm for the reef and turns the coral white. It is happening with increasing frequency so that the coral is damaged beyond where it can recover. He hopes people will be inspired, moved and motivated by Wild Images, Wild Life.

“I’d like my audience to feel they’ve been entertained, and that I’ve offered some fresh insights into how and why we film wildlife. If you like those ten minutes ‘diaries’ at the end of the big shows, then think of this as an extended version. But I also hope people take away a fresh sense of connection to our planet, an empathy with it so they see the urgency about tackling climate change. The decisions we have to take will be difficult, but there are solutions and I’ll be looking at them too.”

Allen has worked with Sir David Attenborough on such landmark series as The Blue Planet, Planet Earth, Life and Frozen Planet. He describes him as a remarkable human being and was privileged to get to know him in 1981.

“In 1981, David was filming for The Living Planet, his follow-up series to Life on Earth, and he with his film crew hitched a ride on the Royal Navy’s HMS Endurance to the Antarctic. The ship had scheduled a visit to the island where I was working as a scientist and diver. It fell to me to take the film crew to places where they would get the best views of the wildlife. Watching David’s cameraman, I thought, “He’s doing all the things I enjoy. That what I want to do next” David and the others very generously gave me advice about how the television business operated.”

Sir David took Allen under his wing.

“A penguin’s wing, yes you could say that. I remember one night on base he said “If I want to go to Africa, there are a dozen people I can phone about filming elephants, chimps, whatever. But if I come back to film in Antarctica, I’ll have to come to you.” It left me thinking maybe I did have some kind of unique selling point. I had the chance to go back to the Antarctic the following winter, a different base, no diving but a colony of emperor penguins that were accessible through the winter. So I decided to take a movie camera with me. I contacted Jeffery Boswall, a producer at the BBC who was just beginning a series all about birds, and I filmed the emperors for him.”

His footage of emperor penguins went out in a BBC series called Birds for All Seasons, which aired in 1985. That was Allen’s fist major step into the filming business. Fairly quickly, he became known as the guy who did polar things, and for years on end he went to the Arctic and the Antarctic and back again. That gave me him unique perspective. He was seeing things happening to the poles and understanding them in a way that a scientist could.

He is proud of his association with the poles and with Sir David.

“Sir David is the master of communication, so enthusiastic, still SO enthusiastic after sixty-odd years, you can hear it from the intonation in his voice. That’s how he struck me from first meeting. There’s nothing he likes better than being in the company of people who have an interest in natural history. To be on an Antarctic base, as we were in 1981, is probably still his idea of heaven. Being surrounded by all that wildlife, there was clearly such enthusiasm in him and in the whole film crew, I saw the best of the business at work and it absolutely inspired me. A man of the people, for the people, and passionate about the natural world.

“There does seem to be a chemistry between us. So I’d say he and I get on well, the way it’s easy to be in each other’s company. I’ve done two or three series with him, and we’ve always hit it off. We don’t see each other very often, but not long ago I was going to be in London for an afternoon, so I phoned him on spec. “I’ll be in London this afternoon. Can I come and see you?” He replied, “Sure, drop by for tea.” I thought, David, it’ll just be grand to have a wee catch up.

“He is a wonderful person. But he would be a lovely man, no matter what his status was. Being very famous has not changed him at all. David will make the best of whatever situation he finds himself. He will take whatever comes.”

Sir David has been equally enraptured with Allen’s work and famously said: ‘Wildlife cameramen don’t come much more special than Doug Allan’. He made the remark in 2012 when BBC Scotland was making a series called Wildlife Cameramen at Work. While it was in production, Allen asked one of the directors when the show was going out. They replied that it was likely only to be filmed in Scotland, but if they could get someone big involved, all the other regional BBC networks would. Allen dropped Sir David a line.

He remembers: “It was classic David. He wrote back to me in broad Scots “Dear Doug, dinnae fash yersel, it will be my pleasure to help”. I bore that letter aloft back to the producer and so it happened.

“Then he did me the great honour of saying in his commentary that: “Wildlife cameramen don’t come much more special than Doug Allan.” He often tweaked his commentaries, and he must have put that in to make it personal. That’s very typical of him.

“People still latch onto that quote. It’ll be the one on my gravestone... in fact maybe I could embed a motion detector, microchip and speaker in the granite so out come the actual spoken words whenever anyone approaches…”

Allen has achieved much in his career, having started out as a biologist for the British Antarctic Survey in 1976. In those days, crews would go off with a suitcase full of money and nobody knew exactly when they would be back. The norm was to go on a shoot for four weeks without seeing a single frame of what they’d shot until you got back.

He has achieved a number of firsts – and is proud of having done so.

“The Holy Grail is to film something new and spectacular. On Life in the Freezer, myself and Pete Scoones were the first ever to film a leopard seal underwater. They have a fearsome reputation, but we managed to nail a great sequence. On Dream Island, we discovered a gulley where the leopard seals would wait to prey on penguin chicks. We had four camera people by that gulley for a week – two underwater and two on the surface. We didn’t know how many chances we would get. We captured the extra drama of the young penguins wobbling towards the gulley across the ice. In the end, we got great footage.

“The most perilous was for a documentary called Wildlife Special: Polar Bear in 1996, we wanted to film polar bears swimming. It was easy enough shooting them on the surface because we could stand on an ice floe and use long lenses. But underwater was a challenge. We spent several days on the water in a boat, hoping we could find a polar bear that would let us get close enough to film. When we did find one, I would slip into the water ahead of it to try for underwater shots. It was pretty hairy because polar bears hunt seals in the water, and I might have been mistaken for one.

“We also discovered that even when they were relaxed, they were still swimming way faster than I could keep up with underwater. So we changed tactics, and used a small underwater camera on the end of a pole. And one glassy calm day, we found a polar bear swimming but so chilled out that he allowed us to slip that pole virtually between his front legs as we gently motored alongside him in the boat. You get a great thrill when you know you’ve nailed something spectacular like that."