Underground miracle which foiled Hitler's bombers

At last the secret could be revealed – but it still wasn't a good idea to ask too many questions.

It was in 1943 that Star readers learned the cunning plan to evade the attention of Hitler's bombers. Tucked away in a Midlands hillside a great factory had been created turning out aircraft engines for the war effort.

The site was Drakelow Tunnels, an underground complex that was to remain hush-hush for many years, during which it has seen different incarnations, as a storage depot, a regional seat of government in the event of nuclear war, a visitor attraction, a venue for ghost hunts, and even in 2013 a cannabis factory – that was illegal, of course, but added to the folklore of the site.

The story continues, as in March this year planning permission was given, after an appeal, to turn Drakelow Tunnels, beneath Kingsford Country Park, between Kinver and Wolverley, into a bonded warehouse and wine store, with part of the tunnel space being used as a museum.

But let's turn the clock back to April 6, 1943, when Star readers were told, no doubt for the first time, about the existence of the top secret Drakelow site – naturally the wartime report was vague as to the location in case the Luftwaffe was reading, describing it as "somewhere in the Midlands".

Back then we sent "Our Special Correspondent" to investigate, presumably on the invitation of the authorities, or if not, at least with their permission.

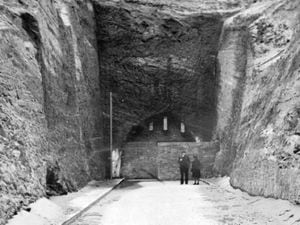

"Walking down a cutting to an opening in a wooded hillside somewhere in the Midlands, I found myself one morning this week not in storybook fairyland, but in a wonderland of modern production – an underground aero engine factory," our special correspondent reported.

"Quarried out of the natural rock, wide tunnels or main roads stretch far into the hill and the countless bays which open out of them make a network of machine shops.

"Here, in this hillside, once pitted with cave dwellings, is a complete world in itself, 60 to 100 feet below the surface.

"Under the curving roof of solid rock, so hard it needs no shoring, office staff sit at their desks and draughtsmen at their drawing boards.

"In another quarter, given over to welfare, I saw cooks and canteen staffs preparing meals and a confectioner baking buns.

"In the canteens, workers took their meals beneath a domed roof of natural rock. This strange underworld even includes a billiards and games room, a surgery as up-to-date as that of the most modern hospital.

"Sirens are unheeded and production goes on day and night uninterrupted. In the knowledge that no bomb can penetrate to their workshops, employees work confidently and without fear."

It was difficult to believe, our correspondent said, that above were fields and woods.

"Specially designed fluorescent lighting gives the impression of perpetual sunshine, and the matt buff paint with which the sides and roofs of the roads have been sprayed take away any suggestion of caverns."

Although the factory was beneath the surface of the hill, it was on the same level as roads leading to it.

Some workers were brought in by coach, while others whose homes were further afield lived in a hostel built on the surface "just a pleasant walk away from the factory".

Our correspondent didn't dwell on what was actually going on at the factory, but plans for an underground plant had been discussed during the height of the Blitz, and blasting started at Drakelow in 1942 to produce a series of chambers.

By July that year the first 50,000 square foot space was ready,

It was planned to be a shadow company for the Rover car company in Birmingham, which at the time manufactured engines for Bristol Aeroplane Company.

The factory was originally called Drakelow Underground Dispersal Factory, and on completion covered around 250,000 square feet. In 1943 Rover was in full production of aircraft engines, which continued until 1946.

The Americans were there too, with a radio and codebreaking school moving in in 1944.

After the war the tunnels became a depot for old machine tools, and also produced parts for tank engines, and in 1961, as the Cold War deepened, part of Drakelow was converted to a regional seat of government in case of nuclear war.

In 1994, with the Cold War over, the complex was sold off by the government.

Parts of the tunnels still remain powered by light, but some stretches lie in darkness, out-of-bounds, and have been left to history.

As with any strange place, stories of ghosts have emerged over the years, which add to their mystique. There have been stories of strange music and of security guards’ dogs going wild at intruders that cannot be seen. Visitors apparently feel sudden drops of temperature.

In 2014, Drakelow was visited by Living TV’s paranormal investigators Most Haunted, where they conducted and investigation into the unexplained happenings within the tunnels.

The crew, led by Yvette Fielding, was sealed off from the outside world and locked in the complex at their own request for 48 hours. Their first night was spent in the old Rover Shadow Factory focusing on Tunnel 1, their second night was spent in the RGHQ Nuclear Bunker.

When they emerged from the tunnels 48 hours later they were described as “extremely distressed” after sensing another presence around them.

Of course stories of ghosts are great to retell and even better for tourism. But the tunnels have witnessed tragedy in the past.

During their construction, several accidents occurred, resulting in the deaths of six men and one woman.

The first and most traumatic series of deaths happened on October 31 1941, as a roof collapsed in Tunnel 1.

Whilst blasting in Tunnel 1, the roof suddenly caved in without warning.

Mr Harry Depper and two of his colleagues who were working in the tunnel were crushed to death by the falling rock.

Mr Depper was buried in a local cemetery on November 5, 1941, but sadly the names of his two colleagues are not known.

Intriguing stories surrounding Drakelow go as deep as the tunnels themselves.

Many can be found on the website drakelow-tunnels.co.uk